Uterine Melancholy & A Slight Hysterical Tendency

a spoonful of isolation helps the patriarchy go down

Uterine Melancholy: The Origin of Hysteria & Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Life Beyond The Yellow Wallpaper

Charlotte Perkins Gilman was a feminist, humanist, sociologist, novelist, poet, and essayist. She was born in Hartford, Connecticut (hello, Rory Gilmore) in 1860. Even though she wrote hundreds of short stories and thousands of essays, The Yellow Wallpaper is her most famous work.

Gilman was a designer herself, having attended Rhode Island School of Design for two years (1878-80). I like to think that her descriptions of the yellow wallpaper came from some terrible designs she had seen during her time as an illustrator. Just to think that she once saw a design so disgusting that she wrote it was “one of those sprawling flamboyant patterns committing every artistic sin” and how “when you follow the lame, uncertain curves for a little distance they suddenly commit suicide—plunge off at outrageous angles, destroy themselves in unheard-of contradictions.”

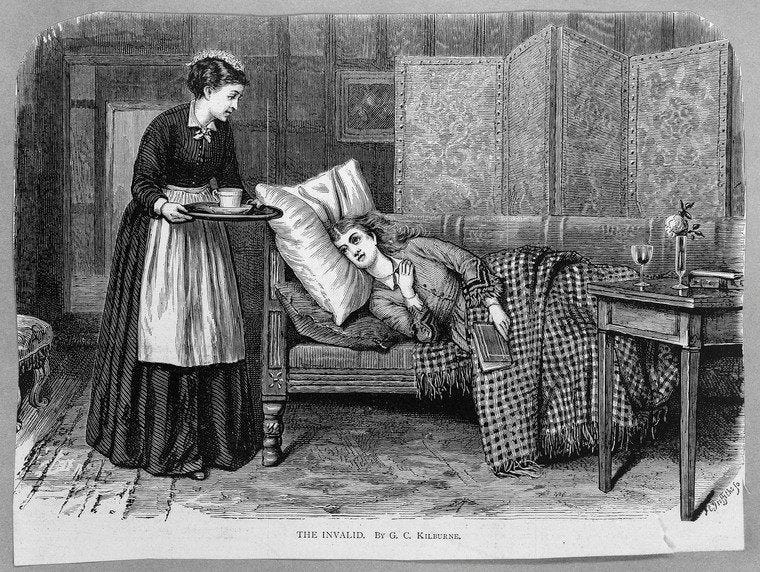

After the birth of her first and only child, Gilman experienced what we now know as post-partum depression, and it served as inspiration for The Yellow Wallpaper. At the time, this was known as a ‘nervous condition’ or female hysteria. The treatment was a rest cure in which patients were not allowed to do work of any kind or overexert themselves in any way. I once wrote a 27-page paper on the oppression of women which included female hysteria so I could go on and on about the origins of the word. To quote myself:

“...the first account of hysteria can be dated back to Egypt in the second millennium BC, where the cause of such an illness is the traveling of the uterus, which Freud reiterates with globus hystericus (traveling uterus).”

This supposed woman’s madness was believed to be due to a lack of orgasms and “uterine melancholy.” In ancient Greece, treatments for uterine melancholy included “hellebore, mint, laudanum, belladonna extract, valerian, and other herbs”. The virgins of Argos were treated with hellebore because they “refused to honor the phallus and fled to the mountains.”

Though rest cures were prescribed for soldiers, they were almost exclusively prescribed for women. Perhaps the rest cures were simply another way for the patriarchy to oppress women, further alienate women from each other, and keep them in submission.

The Yellow Wallpaper is a commentary on the patriarchy, a protest about restrictive domestic roles. The belief that “there is no reason to suffer” is enough to satisfy her husband, and he continuously tries to silence her complaints. One has to wonder if John knew he was gaslighting the protagonist or if he really thought he was doing what was best for her.

Yellow is generally associated with happy and positive emotions, so the color choice here is interesting. The unconventional association makes it even more powerful. The moon, of course, symbolizes femininity but also lunacy. I like the use of it in the story as a literary device to communicate the protagonist’s descent into madness. It is only when the earth turns to darkness that the yellow wallpaper reveals itself to the protagonist as some sort of jailor.

Gilman later married her second husband, George Houghton Gilman in 1900. Unlike her first marriage, her marriage to Gilman was—apparently—a supportive and loving one. But she did much more than write, raise a daughter, navigate marriage, and live with an often debilitating mental illness. Charlotte Perkins Gilman promoted many social reform movements, including women’s suffrage. Her book, Women and Economics (1898), was widely received and translated into seven languages. As mentioned in a previous post, Gilman ran her own magazine called The Forerunner.

Despite falling victim to the stigmas of her time, Charlotte Perkins Gilman made her own way in the world and went on to live a fulfilling life. It’s important to understand The Yellow Wallpaper in the context of her life so that today we can sit here and read this brilliant short story, but also think about how our understanding of it has shifted throughout the last century or so.

<3 Didi

A Slight Hysterical Tendency

The Yellow Wall-Paper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman is a feminist classic. It tackles the issues of womanhood, patriarchy, postpartum depression, motherhood, creativity, and many more. The symbolism speaks volumes, even to a modern-day reader. A desolate woman locked up in a room to “heal from hysteria,” a condition misogynistic in its every aspect – the term having roots in the Greek word hystera, meaning womb. And hysteria assigned only to depressed, wild, or anxious women. The nameless protagonist has nothing else to do than to interpret the ugly paper on the wall, starting to place her own meanings on it, much like a reader of a textual story might do.

What interests me the most in the short story is the infantilization of our beloved main character, who doesn’t even carry a name of her own. Her husband takes care of her (being a physician) by locking her up and forbidding her creative outlet, since how risqué is a woman who writes down her thoughts… is she… thinking… with her own brain? Scandalous! There aren’t many things more frightening than a woman with a strong sense of her own identity, right?

We find the main character in a room with an ugly wall-paper, a room that used to be a nursery. A reader could interpret the room as a symbol for her body, the wall-paper as a symbol for her mind, and the beautiful, lush garden a symbol for “freedom,” where children can play, but women only creep. She speaks about the woman who lives in the wall-paper: “I think that woman gets out in the daytime!” (p.20) And: “Most women do not creep by daylight” (p. 20).

A reader might draw a conclusion that back in their time, most women had to take part in the patriarchal play during the day. To be oneself, one had to wait for nighttime since, in the dark, in the moon-shaped pool of silver light, one might become one’s true self. When no one can see you but the clouded night sky lurking in from behind a soft curtain. There, creeping from room to room, you may act as yourself when the societal norms are asleep. You become a person, an identity, a story, much more interesting than the gendered act during the daytime.

In the story, the room’s key is in the hands of the husband, and when finally, he and his sister come to the room, trying to figure out the wall-paper, the main character feels it intrusive: “But I know she was studying that pattern, and I am determined that nobody shall find it out but myself!” (p. 17) A woman held hostage by patriarchy would understandably want to define herself outside the realms of the world of structure created by men.

On page 4, the main character describes the room. It has been a “nursery first and then playroom and gymnasium.” The stages of the usage of the room could be read as describing the stages of a woman’s body until the stage where we find our main character, suffering from postpartum depression. The woman is expected to blossom into motherhood but struggles with hormonal changes and feels the last strip of her autonomy taken away. Since postpartum depression wasn’t acknowledged in her time, she’s been diagnosed (by her husband) to suffer from hysteria. Although that gets her locked up in the ugly room, she is happy that it is her in the room with the wall-paper, not her kid.

Her husband, John, forces her wife to bedrest, in a foreign house, in an old nursery, as if to reduce her to the level of a child again. She cannot write, for too much imagination can make you wild. Or to dream about liberty and autonomy. He cares for her as he sees best. “What is it, little girl,” (p. 14) utters John to his wife. A short sentence where the infantilization culminates. He keeps going: “’Bless her little heart!’ said he with a big hug, ‘she shall be as sick as she pleases!’” As if her emotional dread and awakening were only a nasty nightmare a kid would wake up from. A woman whose body has just turned itself inside out to birth new life is treated like an infant who’s helpless and weak.

But finding yourself trapped like that is a nightmare. The house and the room itself could be read as something way more eerie than an old nursery. Since there are locks on the doors, scratches on the walls and the bed is nailed to the floor. The protagonist finds company from the woman trapped inside the wall-paper and describes her: “By daylight she is subdued, quiet. I fancy it is the pattern that keeps her so still” (p. 16). And once the moonlight falls, the woman in the wall-paper starts shaking her bars, trying to get free. The moon casts its feminine light on the oppression women are under in the society of their time. Our main character finally admits: “The fact is I am getting a little afraid of John” (p. 17). John represents the patriarchal pattern, treating women like children but grown enough to give you a bit of pleasure, a few babies, and a lot of trouble.

And it’s not only her husband. John’s sister is acting as a keeper of the patriarchal rules, making sure everybody’s playing their part, although becoming fascinated by the paper herself too. The sister, Jennie, wants the protagonist to get well, meaning back to her role as the lady of the house. But our protagonist is too aware of the new realm she has discovered. And once you are made aware of something, shutting it down can be impossible: “But I am here, and no person touches this paper but me, – not alive!” (p. 23).

On page 5 she tells us her concern: “Nobody would believe what an effort it is to do what little I am able, – to dress and entertain, and order things.” What kills the mind of this woman is not her womb causing hysteria, it is not her childlike imagination, it is the system that robs women of their autonomy and any chance to excite their mind with intellectual acts, with real conversation, with real relationship in beautiful nature, outside of the pattern, the sickly, yellow smell of a rotting system.

The room should be hers to decorate, hers to lock up if she feels like it. Hers to build a nursery or a study or a bedroom. The walls should be hers to narrate or redo as she pleases. And the garden should be hers to walk around in, head held high, during day or night. Not creeping, not acting only as someone’s wife or mother, but experiencing the entire world as if it belongs to her, because it does. It does. And it is lush and evergreen.

<3 Jonna