Longing For That Foreign Place

I’ve wanted to read both Kafka’s diaries and letters for a long time. Every single quote I ever saw from his diaries or letters resonated so deeply, which is why I was happy that Letters to Milena won our February book poll.

Reading this collection felt like looking into a mirror of my own romantic relationship. In the introduction, Phillip Boehm writes what is so special about this collection is that “the letters themselves do not merely reflect the stages of the relationship, they are the relationship.” And, if one hundred years from now, someone unearths the messages between me and my partner, they’d say the same thing—at least for what has transpired so far. The most poignant of them would be the letters i.e. extra long Goodreads messages and thousand-word emails exchanged when we first met. And just one single handwritten letter, lost to the ether due to the pandemic and post office strikes.

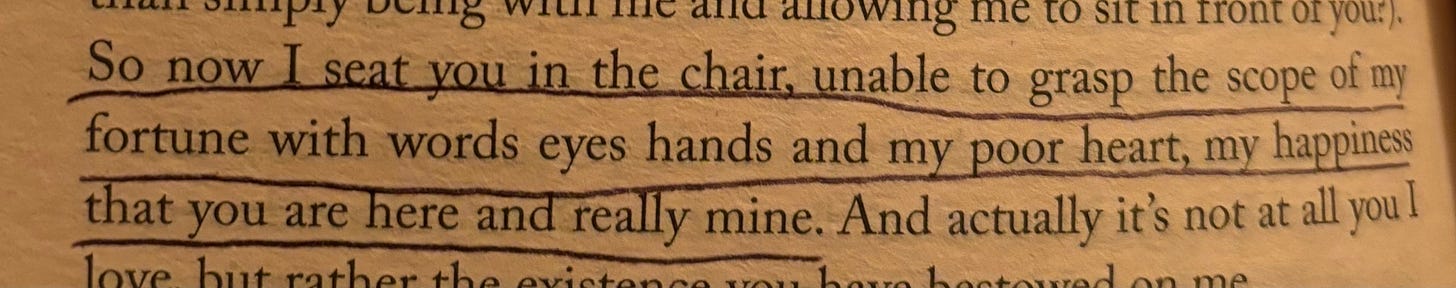

“I’m tired, can’t think of a thing, and my sole wish is to lay my head in your lap, feel your hand on my head, and stay that way through all eternity” (p.100).

By the time I was halfway through the collection, I knew it had made itself onto the list of books that make me who I am. In a way it felt like I was reading my own letters. I only wish that we got to read Milena’s side of the correspondence as well (Kafka burned them and told Milena to do the same, but if she had I wouldn’t be sitting here writing this review right now).

There are so many ways of saying I love you without saying it:

“How has your life changed since you spoke with the doctor—that is the main question.” (p. 15)

“Do I have to have the nourishment of your presence?” (p. 110)

“You’re lying in bed? Who’s bringing you your meals? What kind of meals?” (p. 137)

“I’ve been lying down on the sofa for two hours now, scarcely thinking of anything but you” (p. 203)

“Is your general situation good, bearable?” (p. 232)

Jesenská and Kafka met when she was translating some of his works into Czech. Their letters quickly developed from formal and impersonal to incredibly intimate. So much so that Kafka sent his diaries to her. Over the course of their relationship, Milena was in an open marriage to Ernst Pollak. It was actually her husband who introduced Milena to Kafka.

So many of Kafka’s letters and small details reminded me of myself. His frustrations about work life, his yearning, both his and Milena’s poor health. Maybe it’s just me, but I think finding this kind of emotionally intimate and vulnerable compatibility in another person is very rare. My heart aches knowing they didn’t have much time together at all, and the end filled with so much anguish.

That yearning for someone who isn’t physically with you even in the same country is one I’m all too familiar with not just relating to my relationship but my whole life—growing up outside of my home country and dreaming of a land far away with the type of pebble-at-the-bottom-of-the-mattress discomfort of knowing I’ll never quite feel like I’ll belong anywhere but longing for that foreign place and otherworldly feeling anyway.

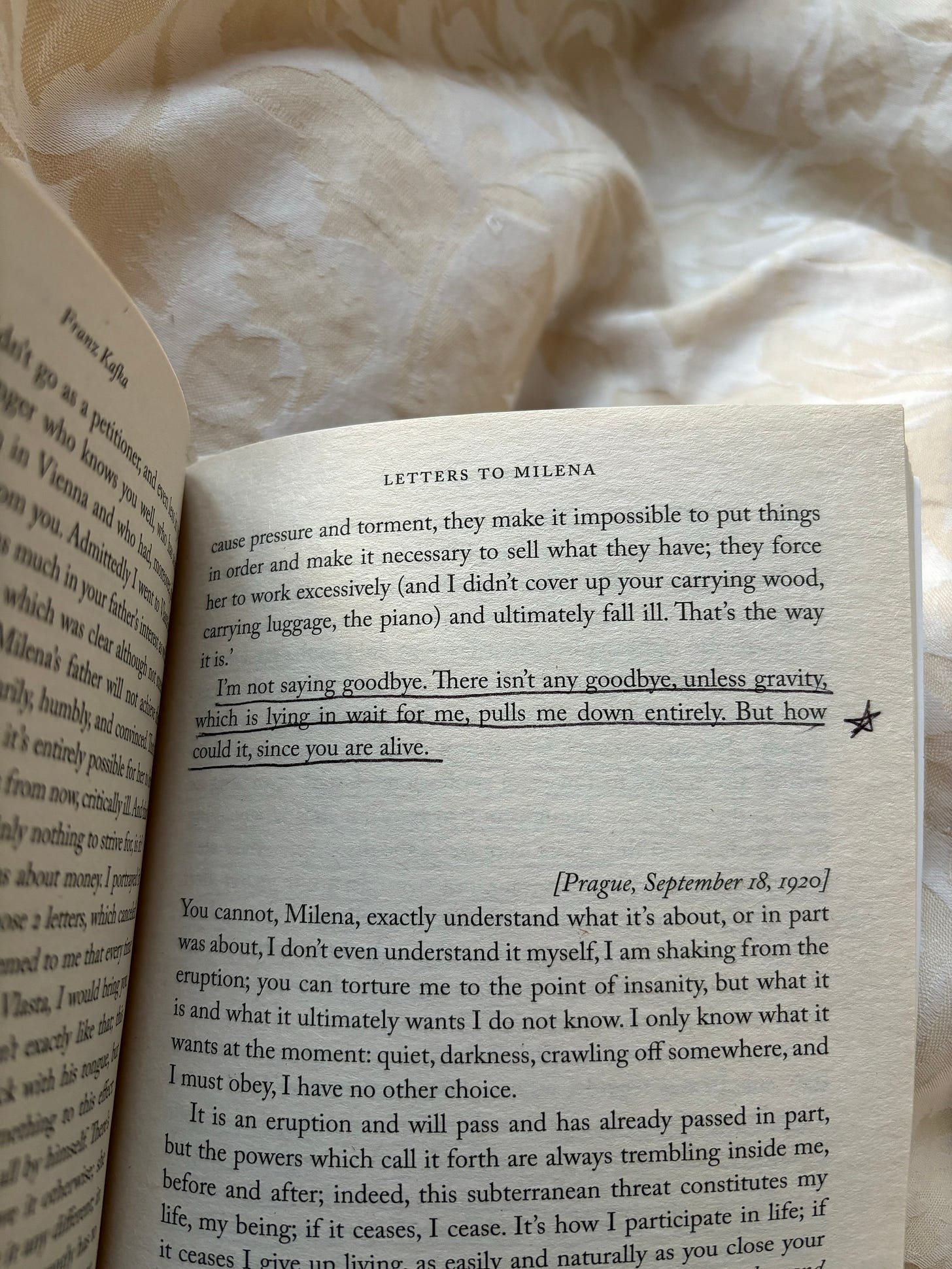

Kafka’s letters were filled with unwavering affection. But that’s just the thing. It wavers. Slightly at first, with little tremors but then with increasing intensity as the months passed. The bulk of their relationship were in those first seven months. But their entire relationship lasted a little over two years, and Kafka died a year later in a sanatorium. They only met up with each other three times. The most heartbreaking part is seeing Kafka revert from the familiar du back to the formal sie in his later letters (meaning “you” in German). And from no salutation back to “Dear Frau Milena.” I can’t remember the last time a book made me cry this much. At several parts of the book, not just this.

“I wouldn’t have a thing, not even my name, since I’ve given that to you as well” (p. 183).

If you’ve been wanting to read Kafka’s letters for a while, this is your sign to finally do it.

<3 D

Kafka and the Illusion of Earthly Love

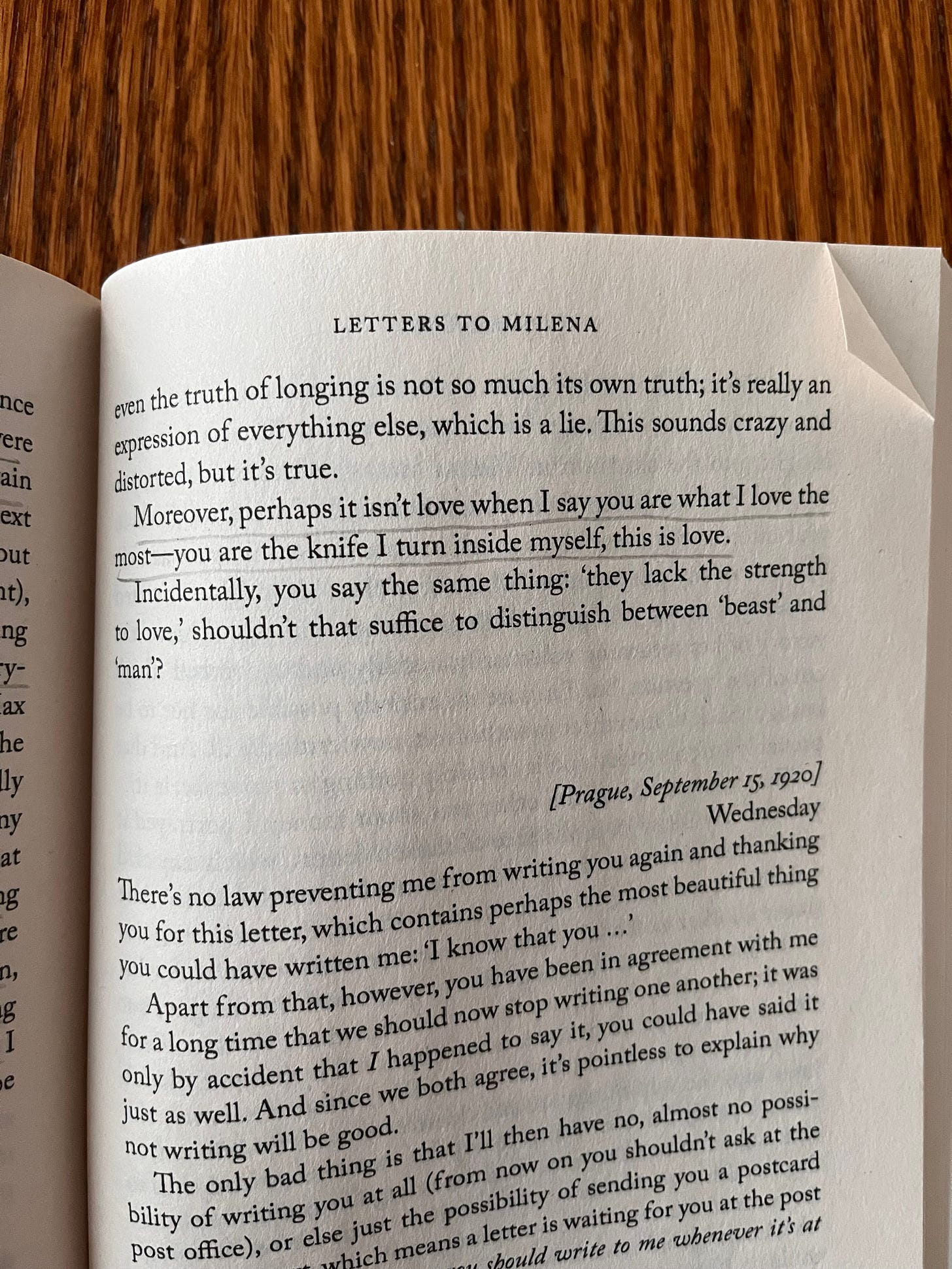

“Moreover, perhaps it isn’t love when I say you are what I love the most–you are the knife I turn inside myself, this is love.” (P. 191)

Kafka’s letters to Milena are beautiful, intimate, and heartbreaking. To witness love born from words alone—without touch, without even reading one another’s body language—is extraordinary. I truly believe in love that writes itself into existence. Especially when the affair involves one or more authors, poets, or those who live within language.

Writing letters (or in today’s world, long messages, emails) is to expose yourself to someone whose presence is both otherworldly and constant, like a ghost. You imagine them beside you, picturing the way their hands move when annoyed, the way their eyes rest on you if only they could see you in the flesh. Half of this love may live in the imagination—but is it any less real? We exist not only within ourselves but also within the perceptions of others. And yet, do those perceptions ever truly reach us? Do they touch our innermost selves? I doubt it. Do we even reach ourselves? Perhaps the core of being human is to remain an enigma, nature witnessing itself yet never capturing its own image fully.

We talk of love. And lust. And that tender feeling of touching someone so lightly you come to know the soft fuzz on their skin. This is love in the flesh: the craters of life already lived, the mark where a scar once rested, now healed.

Love leaves a mark. But is it always love we speak of? Or is it something greater? Magic?

Kafka’s love for Milena is evident in his letters—it shines through his care for her well-being, his acceptance that her presence, even if only in thought, is enough. To love in a way that is inherently lonely. And that is the most striking part of these letters: the acceptance. Of love. Of the human condition.

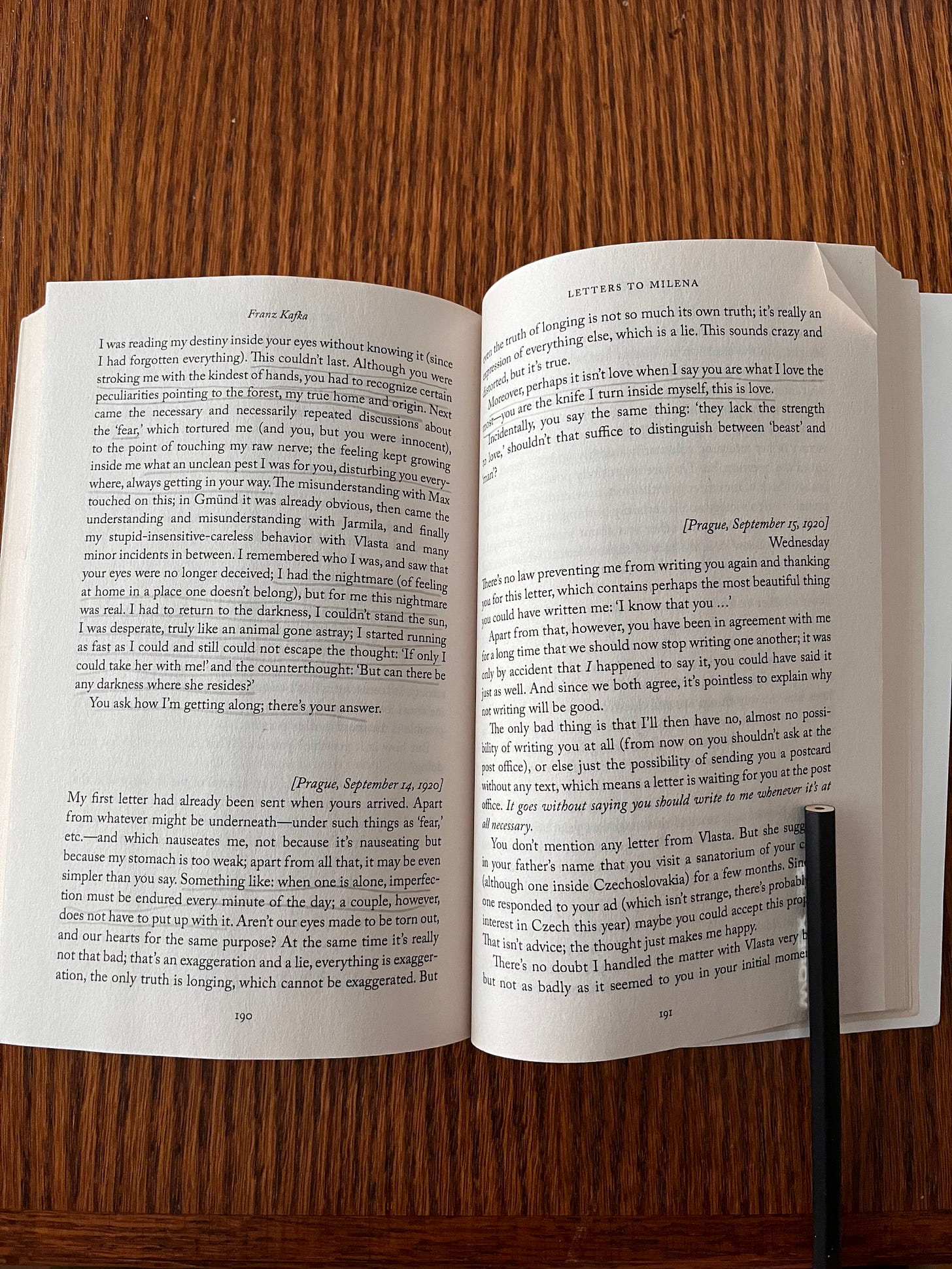

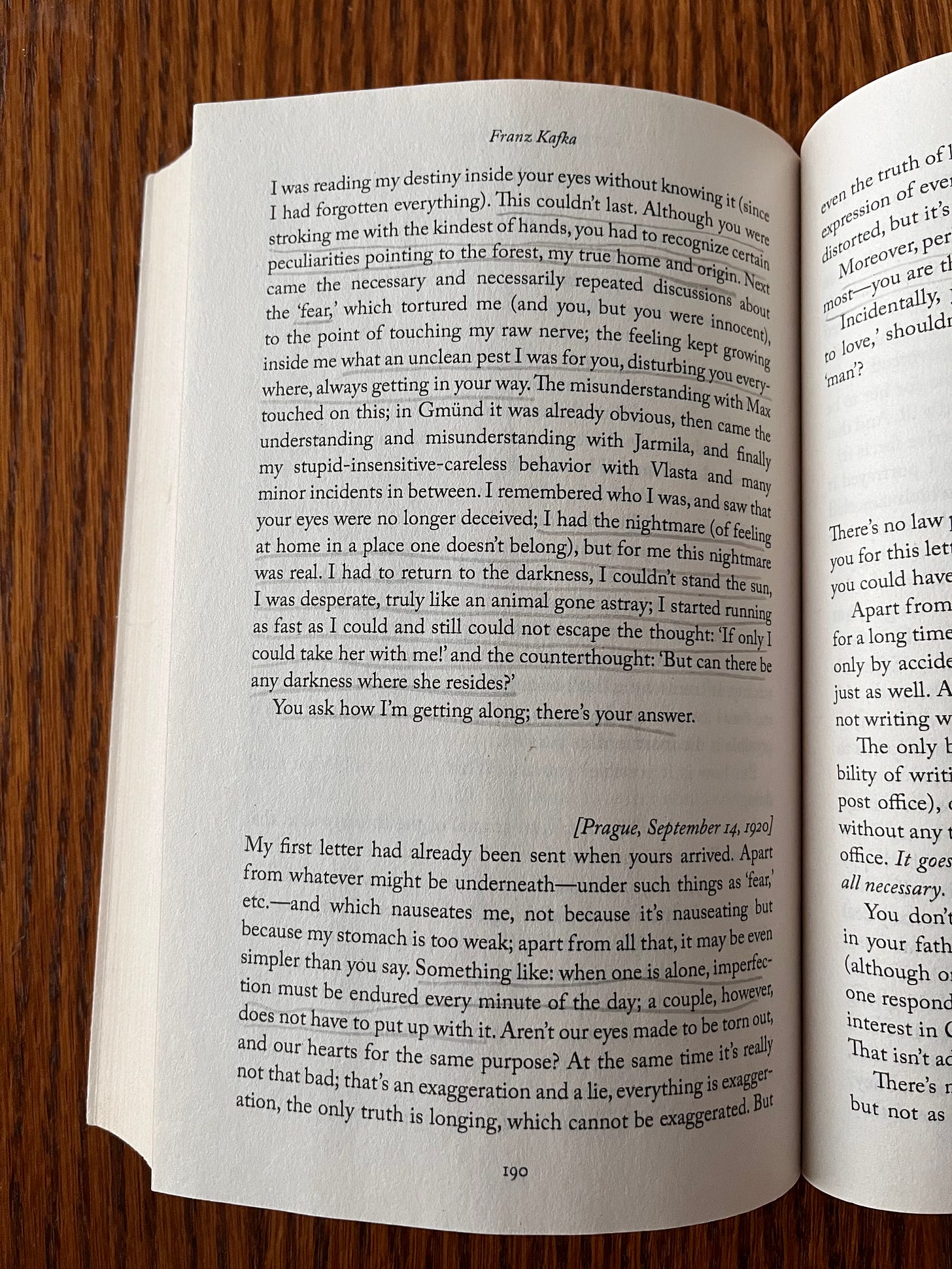

“This couldn’t last. Although you were stroking me with the kindest of hands, you had to recognize certain peculiarities pointing to the forest, my true home and origin.” (P. 190)

Perhaps this unnamable feeling, residing beside love, is the discovery of home within another person. Maybe we all carry fragile pieces of soul, fragments of some distant cosmic place. These peculiarities set us apart, yet make us lonely—until we find another with the same delicate fractures, someone who recognizes the beauty in what once brought us shame.

But what happens when we bring this into the real world? When we try to name it love? Love as we know it—burnt toast, shared laughter, arguments, exhaustion. Some find both realms within one person, but I doubt that is common. Many choose the love we understand, the love that is safe, solid, tangible. But when we force this ethereal bond into the same mold, it collapses.

And then it is all ruined. Our delicate sensibilities, once sacred, are now shamed: “[...] what an unclean pest I was for you, disturbing you everywhere, always getting in your way.” (P. 190)

Who wouldn’t dream of making the extraordinary ordinary? But some loves, some beings, cannot survive the weight of daily existence. And so, like Kafka, you sit by the window, wondering if someone else is making them the happiest they’ve ever been. And you wish it so. And you wish it not. Their laughter could sustain you, feed you like a mother-bird, it could lift you so close to the sun that God itself would create a new world through you. But you accept it. The loss woven into the claiming of a ghost-lover. You dream of their hairbrush, their collarbones, their Sunday rest. But to make them yours would be to make them ordinary. Some call the unearthly to be the highest form of love, but if it isn’t love as we know it; is it actually only yearning for the godly acceptance?

Some of us must live in our dreams. Who would create art if no one stayed otherworldly? Even if it means being alone? With the wild pulse of the world!

“I had the nightmare (of feeling at home in a place one doesn’t belong), but for me this nightmare was real. I had to return to the darkness, I couldn’t stand the sun, I was desperate, truly like an animal gone astray; I started running as fast as I could and still could not escape the thought: ‘If only I could take her with me!’ and the counterthought: ‘But can there be any darkness where she resides?’

You ask how I’m getting along; there’s your answer.” (P. 190)

The realm of the unseen, where everything dissolves and is reborn, can be dark. To exist within this invisible sacred space is to meet the dead constantly, to carry the scent of acceptance—of life, of death, of love, of losing it all. This melancholy draws others in, like a mirror reflecting them as beautiful, not distorted but real, and still lovable. For you see them, and you love them—for a moment, for eternity. You love them as they come, and you love them as they go. And you accept it.

To exist in the act of dissolving and birthing, to be a vessel of creation, to gain and let go and still be whole—this is the price of your life. Of your sensibilities. Of your wild nature. You accept that none of it has a name. Without a name, you cannot share the echoing realm within you. So, you keep writing. You try to name it. Just as humans have done for centuries.

“You are the knife I turn inside myself.” It is greater than love. Less tangible. Less necessary, perhaps. It is the meeting of gods, of seeds, of eternities. Your invisible hands brushing against ghostly fingers. And that trembling sensation right before sleep, when loneliness dissolves for just a moment—someone has come to soothe your tender, battered self. But then morning arrives, and all good things must go.

“To resort to black magic at night hastily, panting, helpless, demonically possessed—in order to capture what every day gives freely to open eyes! [...] This is why I’m so grateful (to you and to everything), and so it’s ‘natural’ I am extremely calm and extremely uncalm, extremely constrained and extremely free whenever I’m next to you. This is also why, following this realization, I have renounced all other life. Look into my eyes!” (P. 148)

Kafka pleads with Milena to look into his eyes—into the portal. Perhaps she did. Perhaps she was lost within it. But if you are lost together, how dangerous can it be? Like running through a field at midsummer. To fall when Earth comes alive and catches you like a dream—which is to create magic. What is the greater word to love? To promise to remember? To promise to dream of her, even when sleep pushes you away?

And me? I do not know love. It has never belonged to me. But I know magic. It has been my nocturnal ache, my hour of hope. Whatever exists between Kafka and Milena is vast enough to fill an entire life. So alive that bodies become unnecessary. No need to hurry.

Kafka writes: “And how can I fly away if we are holding hands? And what good is it for us to both fly away?” (P. 122)

Perhaps he found a home in the abyss of primal wind, where echoes reside and worlds rise and fall. Would I invite a lover there? No, of course not. I would want you to remain where touch and laughter keep you tethered. Where the hum of cars and nighttime television guard you from the sense of unbelonging. I wouldn’t even share it. For how could my darkness light up your day? If anything, it could only flicker through the night. And that’s the time for your peaceful rest. If anything, you should dream of me. Let me stay with you in the dream. It would be beautiful—it would be yours, after all. I would be yours, after all.

Kafka sensed the immensity of the world and, from that knowing, created. It is not love. It is purer, more childlike, more honest. Why name it love? Let us remain soft. Let us recognize one another in the quiet hour of beating hearts and then let go. For the best I could ever give you is this: my creation, held in my hands, reaching toward you, knowing you will see it all.

That no artist ever knew what to call it.

So I gave it your name.

<3 J

Order Tender Philosophia on Bookshop! (you get a discount here while supporting indie bookstores!)

Order Tender Philosophia on major retailers worldwide!

Add Tender Philosophia on Goodreads, Fable, or Storygraph!

*This post includes affiliate links